image: Wikimedia commons (link).

The preceding post presented evidence to suggest that the ancient wisdom which informs many of the sacred traditions around the world may have had a deep common source, or that while manifesting itself in different outward appearances in different cultures and time periods around the world, one stream can be detected surging through all of them.

In particular, that post and previous posts related to this discussion (such as this one and this one) argue that when these ancient traditions are understood to be esoteric and allegorical in nature, then their deeper unity can be perceived: different metaphors may be employed, but upon closer examination it is found that these varying metaphors are all attempting to convey a very similar message.

On the other hand, there is abundant evidence to support the conclusion that replacing the esoteric and allegorical approach with an approach that understands these texts primarily as describing literal and historic events and personages leads almost by necessity to divisions and separation and contentions.

These divisions can even lead to a cutting-off from the connection to the universe itself, and to the invisible flow of the universe referred to in some ancient texts as the TAO or the Way (a word which itself may, we saw, be linguistically related to a host of other sacred names around the world, including PTAH, JAH, BUDDHA, MANITOU, and others).

It is both interesting and valuable to examine some of the principles of Taoism and see how they resonate with principles in other ancient cultures seemingly far-removed from ancient China. One well-known passage from the Tao Te Ching, found in the section traditionally numbered 8 out of 81 (although earlier texts only discovered in the last decades of the twentieth century and discussed further below appear to have arranged the sections quite differently), reads as follows:

上 善 若 水

水 善 利 萬 物 而

不 爭

處 眾 人 之 所 惡

故 幾 於 道

居 善 地

心 善 淵

與 善 仁

言 善 信

政 善 治

事 善 能

動 善 時

夫 唯 不 爭

故 無 尤 (link).

This section has been translated:

Best to be like water,

Which benefits the ten thousand things

And does not contend.

It pools where humans disdain to dwell,

Close to the Tao.

Live in a good place.

Keep your mind deep.

Treat others well.

Stand by your word.

Keep good order.

Do the right thing.

Work when it's time.

Only do not contend,

And you will not go wrong.

Translation by Stephen Addiss and Stanley Lombardo (link).

The final character in the first line of traditional characters above, and the first character in the second line, is the symbol for "water":

水

The passage says twice that water "does not contend." This is expressed by the traditional characters

不

and

爭

which mean "not" and "contend," the first symbol sometimes being described as a bird, flying up to a ceiling and not being able to fly out (therefore expressing the concept of "not") and the second symbol being composed of two characters stacked on top of one another, the top character resembling a "claw" and originally carrying that meaning (it looks like a horizontal bar with three "fingers" extending downwards) and the lower character being a symbol for "manual dexterity" and being derived from the basic character for "hand," which looks like this:

手

Thus the symbol for "not contend" or "it does not contend" is composed of a symbol meaning "not" and a symbol that expresses "grasping" or "clawing" or using the hand to seize and clutch and grab.

We can readily appreciate that water in fact does not contend: it is a well-known and oft-stated aphorism that water always "seeks the path of least resistance." Water seeks the lowest places, something that this section of the Tao Te Ching points out, while commenting that these are the places where people (indicated by the symbol

人

in the third line of characters as shown above) "disdain to dwell" -- and then saying that these places are somehow those that are actually "close to the Tao."

This is interesting, because it is at this point that it becomes clear that the text is referring to something more than a literal concept: it is probably not telling us that in order to become "close to the Tao" we have to actually seek out certain low-lying swampy pieces of terrain and crouch down there. The text is referring to something that is invisible, something that is a principle related to the universe and the Way that it operates, through an examination of the principles that we can see in water.

From this rather famous passage from the text, we can perceive that aligning with the Tao seems to have something to do with "not contending," with emulating certain aspects exhibited by water in its efficiency and its lack of "grasping" or "clawing," and with aligning ourselves with the invisible energy of the universe and the direction that it takes us, rather than seeking out the things that are perhaps most highly sought after by society (the comment that water "pools where humans disdain to dwell" indicates that the things most highly valued by society may not always be the best guide or indicator of the direction we want to seek).

The character for the word "Tao" itself is actually composed of the symbol for a road and the symbol for a head (which itself is based upon the symbol for an eye), and appears in the computer version of the symbols in the text cited above in the following manner (you can see it at the end of the fourth line of characters):

道

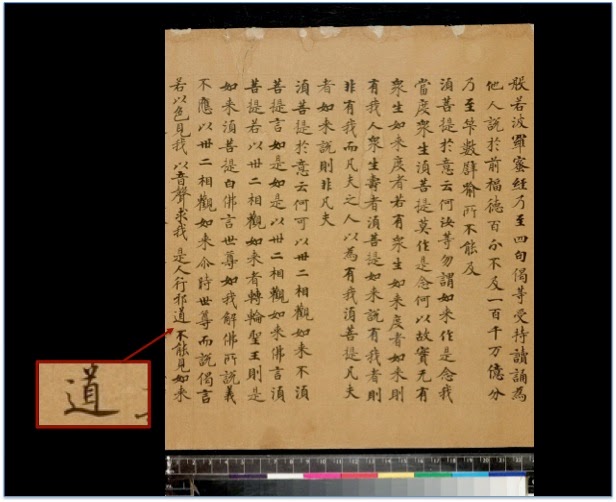

This symbol looks rather prosaic as rendered by a computer, but when written by a calligrapher is a singularly beautiful and expressive character (below is an example from a manuscript of the Tang dynasty, which has been dated as written by a calligrapher in AD 676):

image: Wikimedia commons (link) -- I've taken the liberty of adding a cutout of an enlarged image of the character for "Tao" (Way or Road) from the text, and pointing out its location within the text.

The word usually rendered into English as "Tao" which is indicated by the above character is actually pronounced dao in Mandarin Chinese (poutongwa), and douh in Cantonese (Guangdongwa) and means "way" or "road" (but also "Tao" and is also used to refer to Taoism in general).

It is interesting to think of this "Way" as being somehow akin to the path followed by water, which unerringly seeks out the most efficient and effective and least contentious Way, a Way that has no need for contending -- and then to think about examples in daily life that seem to embody this principle.

For instance, one might think of a motion in a familiar sport, such as basketball or tennis: shooting a basketball is a fairly complex skill, as is striking a tennis ball effectively with a forehand or backhand or an overhand serve. There is a set of motions that is most effortless, most efficient, and generally most effective for shooting, say, a three-point shot in basketball or hitting a powerful forehand in tennis.

However, when we first begin to try to perform these motions (or when we see someone who is just learning to do it, perhaps a child or a teenager or some other beginner), what often happens is that the beginner will find his or her way into using a set of motions which are not the most effective or efficient -- a set of motions which we might say are not, strictly speaking, "good form," but which give the person a sort of "artificial" success.

You might see children who are not quite strong enough to shoot a basketball properly at a full-sized hoop, for example, using a variety of "compensating" motions in order to get the ball to the proper height to go into the basket -- but which you realize are habits that must eventually be corrected as the child gets older and stronger, because they are actually not the most efficient motions or the motions that will produce the most consistently accurate shots, because they actually are motions that "work against each other" in some way.

Sometimes, we ourselves (or people we see who are learning a sport such as basketball or tennis) will "hold on" to these bad habits, because they produce a modicum of success, and we are afraid of losing that success by unlearning those motions and replacing them with the more effective motions. Coaches sometimes see a lot of resistance from a player who is comfortable in some bad habits which the coach knows are holding the player's shot back in certain important ways.

This may be a good example of the concept being expressed about being "like water" and "not contending" -- a shot which is using "bad form" is actually "contending" against gravity or against the principles of physics or some other principles "of the universe" in some way, which holds it back and makes it more awkward and more self-defeating than it should be.

Obviously, this rather "physical" example can then be applied to all kinds of non-physical aspects of our lives in which we are doing things in ways that are "contentious" or "not like water" or "not in alignment with the Tao" and which in doing things that way we create all kinds of "turbulence" between ourselves and those around us, or within ourselves, or both. We can even feel the resistance of the universe itself when we are stubbornly refusing to "align ourselves" with the principles of that flow, just as a tennis or basketball player can often feel the ways in which their refusal to align their shot with the principles of "good form" may be causing them to sabotage their own efforts.

Interestingly enough, calligraphy itself and the painting of traditional Chinese characters can be an expression of alignment with the Tao. Producing beautiful traditional characters such as the page of text from the Tang dynasty shown above requires alignment with certain principles which are every bit as demanding as those required in a basketball or tennis shot, and requires the practitioner to learn how to overcome bad habits and inefficient motions that can be every bit as self-defeating as those which players can develop in any sport. One can do a simple search for the words "Tao" and "calligraphy" on the web and find a host of interesting texts on the subject.

Even more intriguing is the fact that the desired characteristics of Taoist calligraphy are expressed in terms of the human body: the characteristics are categorized into the areas of "bone" (the actual structure and form of the characters, as well as their size and "posture"), of "blood" (the consistency of the ink, which is mixed by the calligrapher using a stick, a stone, and a small amount of water), of "flesh" (the thickness and flow of the strokes themselves, and their proportion in terms of being neither too "fat" nor too "skinny" in their conformation), and of "muscle" (movement, energy, spirit, and vital force) -- see for instance this text among many other possible discussions.

This itself expresses the concept of "microcosm and macrocosm," in that the letters themselves are acting a role as a "microcosm" of the human body and, by extension, the human life lived in alignment with the energy of the Tao or the universal flow. Alvin Boyd Kuhn discussed manifestations of this same principle in regards to the letters of Hebrew and Greek and other writing systems within the esoteric traditions of other ancient civilizations in other parts of the world.

As alluded to above, during the 1970s previously unknown manuscripts containing the text of the Tao Te Ching were discovered in tombs in Ma-wang-tui (also frequently written as Mawangdui). These texts, sometimes known as the "silk texts" because they were written on sheets of silk, date to the middle or even the first part of the second century BC, and were much older than previous extant texts of the Tao Te Ching by about 500 years (since that time, in the 1990s, new and even older texts containing lines from the Tao Te Ching have been found in another tomb, this time on thin bamboo strips).

This discovery prompted one scholar of Chinese language and literature to decide that the Ma-wang-tui texts cast so much new light upon the text of the Tao Te Ching that it was worthy of a new translation and examination: the 1990 translation by Victor H. Mair. Towards the end of his edition, Professor Mair (the Chair of Chinese Language and Literature at the University of Pennsylvania) embarks upon some examination of the resonances within Taoist thought and expression to other ancient sacred texts and thought, including the texts of ancient India.

At one point he makes an extremely important observation concerning a passage from the sixth stanza of the Mundaka Upanishad and the section of the Tao Te Ching traditionally numbered 11 (but numbered 55 in Professor Mair's 1990 translation, based on the Ma-wang-tui texts):

The whole second khanda (section) of the Mudaka Upanisad has so many close parallels to the Tao Te Ching that it deserves the most thorough study by serious students of the Taoist classic. Here I shall cite only a part of the sixth stanza, which bears obvious resemblance to one of the most celebrated images of the Old Master:

Where the channels (nadi) come together

Like spokes in the hub of a wheel,

Therein he (imperishable Brahman as manifested in the individual soul [atman]) moves about

Becoming manifold.

The corresponding passage from the Tao Te Ching (chapter 55, lines 103) has a slightly different application but the common inspiration is evident:

Thirty spokes converge on a single hub,

but it is in the space where there is nothing

that the usefulness of the cart lies.

In one of the earliest Upanisads, the Chandogya, we find an exposition of the microcosmology of the human body that certainly prefigures Taoist notions of a much later period:

A hundred and one are the arteries (nadi) of the heart,

One of them leads up to the crown of the head;

Going upward through that, one becomes immortal (amrta),

The others serve for going in various directions. . . . (translation adapted from Radhakrishnan, p. 501). 156-157.

This correspondence, as Professor Mair makes clear, is most significant and most remarkable. The use of the imagery of spokes is common to both, and both clearly use the metaphor of the spokes of the wheel to refer not only to an aspect of the wider universe but also to the human body and to human life, connecting each of us not only to the universe but specifically to the invisible part of the universe, the "space within the wheel," where the invisible divinity is located, and who is also manifest within the human soul.

Not only does this continue the "macrocosm-microcosm" theme which can be shown to be an absolutely fundamental aspect of virtually all the world's esoteric sacred texts and traditions (including the texts of the Old and New Testament), and not only does the concept of the "hidden divinity" have important connections to the concept of "Namaste and Amen" discussed in numerous previous posts (which also connects to the scriptures of the Bible, as well as to important themes present in ancient Egyptian sacred mythology), but it is very likely that these passages which Professor Mair here focuses upon also contain powerful echoes with the text of the extraordinarily important "Vision of Ezekiel" and the "wheels within wheels," which I have discussed at length as being a metaphorical description of an understanding of the motions of the celestial machinery -- the same understanding which is depicted in the models of the heavens known as armillary spheres.

Note that in both of the passages cited above -- one from the Tao Te Ching and one from the Upanisads -- the metaphor of a wheel with spokes is used, and in the Upanisad it is said that Brahma dwells "therein" or in the center of that wheel, exactly as the Most High is described as being enthroned upon or above the wheels in the Vision of Ezekiel.

In fact, as I explained in the previous examination of the details of the description in the Ezekiel text, there the wheel is specifically described as being composed of "strakes," which is a very precise term from the old craft of wooden wheelmaking, describing the curved outer segments of a wooden wheel -- outer segments which would be a perfect metaphor for the twelve segments belonging to each sign of the zodiac within the great celestial band or "wheel" of the zodiac.

Notice that in the passage from the Tao Te Ching, the number of spokes on the wheel is specifically given as thirty spokes: is it not significant that each of the sections of the zodiac wheel (each of the "strakes," if you will) would have exactly thirty degrees, if there are twelve signs of the zodiac and if the circle is divided into three hundred and sixty measurement units called "degrees"?

Based on these correspondences, it is almost certain that there are direct parallels between the esoteric message being conveyed (albeit using slightly different metaphorical details, and different versions of the divine name) by the ancient texts of the Upanishad, the Hebrew Scriptures, and the Tao Te Ching.

This is all very important, and points to profound connections between the ancient sacred knowledge of the human race, and to the fact that we should all actually be united by our ancient heritage, and not divided.

One very practical implication of the foregoing is the realization that one can learn from and incorporate the profound lessons conveyed by different sacred traditions, because they are all using slightly different expressions to try to point towards the same truths. If one aspect of the metaphor provides better insight, or feels in some way more accessible, there is nothing wrong with learning from it. As we have already seen, Buddhism and Taoism are almost certainly names which have linguistically identical origins, and which probably share the same linguistic heritage with the divine names of JAH and PTAH and MANITOU and many others.

The Tao Te Ching has a unique power of its own, a unique voice in expressing and conveying the ancient wisdom.

It describes the ideas of aligning with the flow of the universe in a way that might be particularly helpful in all kinds of "simple" ways within our day-to-day life.

Thinking about having "efficient good form" in a shot in tennis or basketball as being a good example of "aligning with the flow" and not going against it, we can then think about expressing that same kind of alignment and efficiency and "non-contention" in the way we drive a car, or wash dishes, or open a door, or interact with people around us.

When someone starts "contending" with us, we can see if they are acting in ways that are not aligned with that universal flow, and we can ask ourselves whether that is a good reason to allow ourselves to also get out into contention and turbulence, or if we prefer to seek to stay aligned with the Tao and act more like water in a stream.

Of course, since none of us is perfect and since this material realm is full of systems which seem almost purpose-built to jostle us out of alignment with the Tao, this is a process that can fruitfully provide us with rewarding challenges, even if we are performing what might otherwise seem to be the most mundane of tasks or jobs. And even if we have relative success on one day, we won't become bored because the next day will probably teach us how much we still have to learn in this regard.

Ultimately, as the deeper connections touched on above seem to indicate, I believe that the process of aligning with the Tao that is the subject of the Tao Te Ching involves the awareness of, the acknowledgement of, and some interaction with the reality of the invisible aspect of the universe, and not just its physical forces.

And, as we have seen in many previous posts, this seems to be one of the most central messages of the world's esoteric texts and traditions, all of which I believe should be viewed as our shared inheritance from the remarkable messengers who gave us this sacred ancient wisdom.

Gung-hei faat choih!

恭喜发财